Dossier Soy

Soy is hot. This crop is regularly used in animal feed in Flanders and consumers are also increasingly looking for protein alternatives in the form of soy drinks, puddings, and burgers. But the impact of soy imports on our environment is also a trending topic. If we could eliminate the need for importing soy, the environmental aspect would look completely different. That is why growing soy on Flemish soil is a noble, but not yet reachable goal.

What does ILVO do?

-

In growth chambers, fundamental research is done regarding inoculation techniques and bacterial strains.

In growth chambers, fundamental research is done regarding inoculation techniques and bacterial strains. -

ILVO performs annual variety trials to find the best varieties for cultivation in Flemish agriculture.

ILVO performs annual variety trials to find the best varieties for cultivation in Flemish agriculture. -

The most promising soy varieties are sown on practical trial fields to identify and resolve the pain points..

The most promising soy varieties are sown on practical trial fields to identify and resolve the pain points.. -

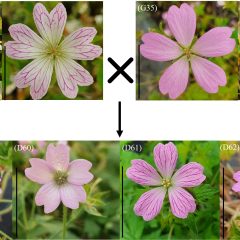

Using breeding, ILVO aims to create new and profitable soy varieties for use in Flanders.

Using breeding, ILVO aims to create new and profitable soy varieties for use in Flanders.

Soy

Soy?

Soy is a subtropical, annual, leguminous plant. The beans of the plant are made up of almost 20% oil and a little less than 80% dry matter, of which about half are proteins. Worldwide, it is one of the most important crops, with South America and the USA as the largest producers. Soybean oil is the most consumed vegetable oil in the world, with soybean meal as a by-product that is used as concentrates in livestock farming.

Global trade in soy. Dark green countries = export, light green countries = import. (Soy barometer 2014)

Soy is a popular crop because the beans have a high protein content and a good protein composition. Of all the vegetable proteins, soy is one of the few that contains all the essential amino acids. In addition, soy is easily digestible and rich in vitamins and minerals.

- 90% of soybeans are pressed for oil

- 10% is processed as a whole bean

The soy plant

The soy plant (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) most likely descended from a wild legume from Central China. The first soybeans were grown in North China approximately 3,000 years ago. After WWII, the United States developed into the largest soy producer. In order to meet the increasing demand from Europe and Asia at the end of the 1960s, production in South America increased enormously.

Soy is a subtropical, annual, leguminous plant that belongs to the Fabaceae family and is known for its beans. These beans are made up of approximately 18% oil and 72% dry matter, of which over half are proteins. The oil from the beans is the most consumed vegetable oil in the world. The remaining meal is the most important source of protein for our livestock. Of all vegetable proteins, the protein composition of soy is the only one that is ‘complete’, i.e. soy contains all the essential amino acids. In addition, soy is easily digestible and rich in vitamins and minerals.

The soy plant can grow up to two meters high, but the common varieties usually remain smaller than one meter. The leaves have three, and very rarely five, leaflets and small purple or white self-pollinating flowers develop in the axils of the leaves. After flowering, pods form with one to four beans. The slightly spherical beans are mostly light yellow but can also be brown, green, or black with a yellow, brown, or black hilum or ‘eye’. The leaves fall off before the pods are ripe.

Growth of a soy plant

Soy in animal feed and human food

Flanders has a high demand for protein-rich fodder due to its intensive livestock farming. And in addition to the now-standard use of soy meal in cattle feed, people themselves are increasingly turning to soy products on store shelves. However, due to the lack of domestically grown, protein-rich crops, Flanders is heavily dependent on soy imports, mainly from South America. This is about 700,000 tons in Belgium.

Is imported soy still a responsible choice?

The high demand for protein-rich crops is causing substantial price increases and market speculation. The price of soy has been rising for years and already peaked at over 500 euros per ton at the end of 2012. Moreover, the import of soy raises social and ecological questions. Large-scale deforestation is being carried out to meet the increasing demand for soy. Deforestation causes a loss of biodiversity, erosion problems, climate change, and also social problems for the population, leading to increasing resistance to these practices. Consumers are also attaching more and more importance to closing the cycles, and are increasingly demanding GMO-free soy, especially in Europe, which is barely cultivated in soy-exporting countries.

It is, therefore, not surprising that there is an increasing demand for locally produced, responsible raw materials. Growing soy in Flanders can meet these needs.

ILVO studies and supports Flemish soybean cultivation

Because of the dependence on imported protein-rich fodder, various initiatives have already been launched. Research has shown that local fodder crops cannot match the nutritional value of soy. That is why trials have been set up in several Western European countries to grow soy in our temperate regions. The first results are already promising and inviting: no disease pressure, proper protein and fat production, and acceptable maturation. Provided that there is sufficient breeding power, with a specific selection for northwest Europe, there is a real chance that it may be possible to grow your own soy with financially worthwhile yields within a few years.

Variety trials

ILVO works in two ways to make profitable and sustainable Flemish soybean cultivation a reality. First, ILVO already started researching soy cultivation in Belgium in 2012. The IWT ‘Introduction of soybean cultivation in Flanders’ project launched on 1 November 2013 with ILVO, KU Leuven, and Inagro as project partners. The potential of soy cultivation for our region was investigated during a four-year study (2013-2017). The focus was mainly on cultivation techniques, variety selection, and crop protection. Profitability was also examined.

Variety trials with several early-maturing soy varieties clearly showed the potential of soy cultivation in our region. From 2014 to 2017, 34 varieties were screened, for which an average yield of approximately 3.5 tons of soybeans/ha (15% moisture) was achieved in the trials. The quality of the beans was of a good level with an average of 39% protein and 21% oil. Flemish soybeans with a protein content of 42% are eligible for processing into human food products by Alpro.

Pioneering project

A second VLAIO project, ‘Towards sustainable and profitable soybean cultivation in Flanders’, was launched on 1 November 2019. Part of that project is to scale up the knowledge gained about soybean cultivation in Flemish soils to a practical environment. That is why ILVO started looking for pioneering farmers who wanted to help speed up the introduction of soy in Flanders. In the spring of 2020, some 35 soy pioneers started growing several hectares of soy for the first time. They were supported by ILVO and Arvesta in all steps of the cultivation, and in return shared their cultivation experiences with ILVO, which was able to identify the practical experiences.

In this way, ILVO combines research into the most optimal varieties, techniques, and crop protection for soybean cultivation in our region with a slow introduction into practical fields. Although the cultivation seems promising, with benefits for the climate and the environment, many bottlenecks still need to be addressed before soy can be introduced as a common crop in Flanders.

Contact an expert

Research projects