Press release Internet-of-Cows: sensors for detection of heat and calving in dairy cattle

Sensors that continuously measure dairy cow behaviors such as lying down, walking, standing, eating and ruminating can predict timing of heat and calving within 2 and 24 hours in advance with high accuracy. The combination of sensors does better than one sensor, especially at the last hours before heat or calving, when a fast response is crucial for both cow and dairy farmer. Researcher Said Benaissa: "This points to the usefulness of the further development of multi-sensor monitoring systems as an alternative to the current one-sensor solutions."

This points to the usefulness of the further development of multi-sensor monitoring systems as an alternative to the current one-sensor solutions.

This PhD research brings dairy farming another step closer to efficient total monitoring. For a sector characterised by larger herds, this offers interesting perspectives.

Monitoring is important but the proliferation of sensors is impractical.

Profitability and being able to meet the growing world demand for milk are two reasons that dairy farms are scaling up. An increasing number of animals offers economies of scale but also creates new challenges. Monitoring individual animals in a large herd is difficult unless sensors complement the visual inspection performed by the dairy farmer. In recent years different monitoring systems have been on the market, but most of these systems are limited to a single production or health aspect and use a single sensor. Dairy farmers must therefore acquire and integrate different systems, which is impractical and increases costs. That is why Mr Benaissa studied the potential of an integrated, multi-sensor monitoring system.

Location of sensors: leg and neck offers best results

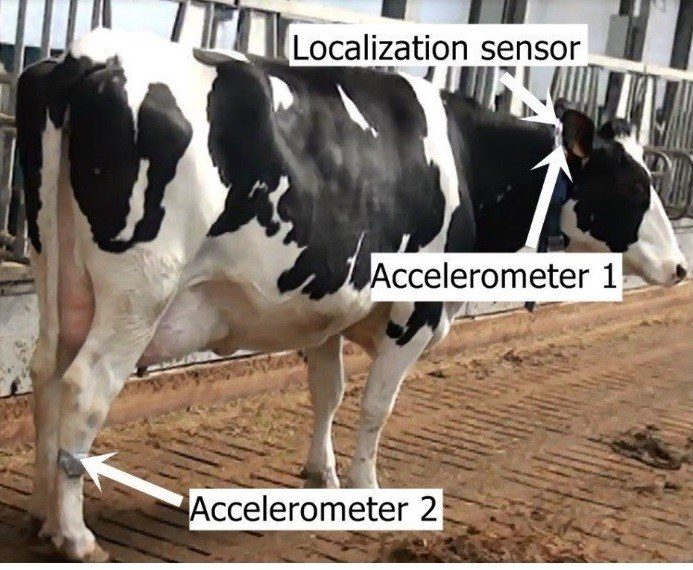

Off-body, on-body and in-body sensors were tested in the barn and in the field, in part to determine the reliability of the signal. Benaissa decided to focus on testing on-body motion sensors. Sensors that measure movement in three directions and transmit to high speed (real time) data proved to be the most interesting for this application. The best position to place them depends on what you want to measure. Benaissa: "If you want to measure your diet patterns, you should choose a sensor at the neck. Are you more interested in lying down, then choose your best for a hoof sensor. If you want total monitoring as in this research, then you need high accuracy and reliability sensors at both neck and hoof."

Data interpretation: Which cow behavior is most relevant?

Finally, Benaissa also added a localization sensor on the neck, to add an extra dimension to the data (in which area of the barn is the cow located and what distances does it travel?) and to check whether the combination of different sensors produces a better result. But before he could answer that question, he had to try to extract meaningful information from more than 200 days of cow data.

Benaissa concentrated on parameters for early detection of heat and calving and made use of machine learning algorithms. These algorithms had to be first refined with knowledge about relevant animal behavior. Which changes in a cow's behavior effectively say something about heat or timing of calving? By analyzing the data he discovered, among other things, that within 24 hours of calving, a cow spends 2 to 3 hours less time on eating and chewing. When it gets closer to calving (6 to 12 hours) it will lie down to rest 2 to 3 times more frequently. The number of steps the cow takes does not show a reliable predictor for calving detection, but does says something about the ideal time of insemination. Two days before the cow becomes fertile, she will begin to wander around more prominently (+-500 steps per 6 hours). She also lies down less (+-4 hours a day) and spend about 2 hours a day less on rumination.

Combination of sensors offers best result

How well do the sensors and algorithms now work for detection of heat and calving? Benaissa tested detection models for each sensor separately and for the combination of sensors.

The combination of one or two motion sensors on neck and/or hoof with a localization sensor on the neck gave the best results. Both the accuracy and sensitivity of the detection showed notable increases. Especially in the later detection phase – 2 to 4 hours for calving or heat, when the farmer needs to be most alert – this makes a big difference. One sensor can detect the ideal timing of insemination with 58-64% accuracy and the time of calving with 40-63% accuracy. By combining the sensors, this increases to 72-87% and 67-79%, respectively.

Benaissa: "This is good news for both the dairy farmer and the cow. Timely and accurate detection of heat are very important for optimal breeding efficiency. It can avoid wastage of sperm and labor and can help a healthy egg to get fertilized. Accurate detection of the time of calving can be important for the further reproduction performance of the cow, its milk production, its well-being and that of the calf."

One step closer to efficient total monitoring

Promotor Bart Sonck (ILVO): "This doctoral research has led to important steps towards integrated monitoring in dairy farming. In the Imec-icon project MoniCow, to which this doctorate belonged, some technological bottlenecks have been solved, such as the robustness of the sensor carriers (collar) and an automatic inductive charging system suitable for stable environments to empty batteries and thus to avoid missed data. A first assessment of the cost-benefit image was also made: according to the researchers, an integrated monitoring system can save the dairy farmer an average of 200 euros per cow per year."

Promoter Frank Tuyttens (ILVO): "For rapid detection of health and welfare problems in animals this is also good news. Clever combinations of complementary sensors can serve to monitor a wide variety of animal parameters. This can help livestock keepers detect (sometimes subtle) changes in behavior and physiology caused by disease, lameness or heat stress far more accurately. The earlier and more accurate the detection, the quicker the farmer can act and the better production losses and animal suffering can be avoided. In the follow-up research we will continue on this."