Press release In dialogue with Flemish livestock farmers about agroecology: "It offers opportunities, but is not a panacea. And the well-known black-and-white classification of farmers does not reflect reality."

Both organic and conventional beef farmers regularly apply agroecological principles. The stereotypical agroecological farmer does not exist. Economic laws that farmers set in motion themselves force them to make compromises in practice. This turns out to be the underexposed Achilles heel for those who want to fully implement agroecology as a model. Those are the conclusions of the PhD of ILVO/UCLouvain researcher Louis Tessier. "Agroecology as an agricultural system ultimately functions in a free market, in which supply and demand, and therefore competition, play a role. On an ecological level, the model is well established; on an economic and social level, it does not provide sufficient answers."

Tessier interviewed some 40 very differently oriented Flemish beef farmers about the relevance of agroecology to their practice. The study uncovered what exactly motivates or holds farmers back. Tessier also took important steps towards making the concept of agroecology 'measurable' in practice. The doctorate provides new insights for the debate on food systems.

Louis Tessier will defend his PhD during an online conference on Thursday, April 22, 2021 at 17:00. You can attend via the link at the bottom of this page.

Agroecology relevant to Flemish beef cattle? Yes it is.

The meat cattle sector in Flanders is under economic and social pressure. One of the solutions put forward in social debates is the application of agroecological principles. But is that really a relevant route for this sector?

Louis Tessier (ILVO/UCLouvain): "Yes and no. My interviews show that there is a wide variety of business models in the beef cattle sector. Remarkably, and contrary to expectations, almost all of them appear to already apply different principles of agroecology, to varying degrees and in different forms. That was true for organic farmers doing short chain and conventional farmers selling through the long chain. Agroecological principles that are already well established include the cultivation of grass-clover mixes, the reuse of stable manure, knowledge sharing among farmers, even natural grazing and private sales. In that sense, agroecology is already relevant today."

Agroecology relevant to Flemish beef cattle? Not quite.

Agroecology as a model runs up against limits, according to Tessier. In particular, scalability is still limited. Agroecology is based on the ideal of a self-sufficient family business that operates in a short chain and is therefore not dependent on the whims of the market. Knowledge sharing and fair cooperation within the production chain are other principles. Tessier: "Whether this is the future for every beef farmer must be questioned. The three biggest pitfalls are mutual competition for customers and land, disagreement on the distribution of benefits between commercial partners and the price war with wholesalers."

First a full belly, then morality.

Tessier: "The organic short-chain cattle farmers I spoke to also have to make regular compromises because of their income. At the end of the day they also have to sell their product. And then they can't ask any price."

A beef farmer testifies, "Even though we are a cooperative, with all these customers behind us, and have our own pricing, it is still farming [...]. So we now ask one euro for a head of lettuce, in the store it's one euro sixty, and then I see colleagues who drop it off at a wholesaler for sixty, seventy or eighty cents, because they want to get rid of it. [...] We can't say 'we're going to ask two euros for our head of lettuce', because then we won't sell it. But if I had to calculate my hours we would have to ask two euros."

Agroecology as we know it today does not yet offer enough answers on the economic and social fronts.

Another beef farmer testifies: "The problem is that we have actually come a long way with agroecology and organic farming. We have improved all kinds of things in the last few decades. But in terms of the economic model, nothing changes. There we are still working with the way we thought in the '70s, hardly anything has been done about it, there is not enough evolution. And the agroecological movement is not taking this sufficiently into account either. They do talk about a social movement, but the economic aspects and business models, for example, are dealt with very little."

Nevertheless, Tessier sees possibilities: "The market economy as we know it today is not a natural law. It is a social fact that all chain partners create and maintain together. This also implies that we do not 'have to' conform to it. And even within the known market dynamics, room can be made for agroecology, especially if we work together." A concrete example? As an individual livestock farmer, for example, you can enter into a sustainable partnership with your so-called competitor to work together with a local supermarket, or even with the local nature movement.

The obstacles: wanting to but not being able to; being able to but not wanting to

Our market logic strongly determines not only the price that cattle farmers can expect for their product, but also their access to production resources such as land. As a result, starting as a beef cattle farmer in Flanders, agroecologically or otherwise, is not within everyone's reach. On the other hand, the own goals and opinions of the farmers who do have the means that, to a large extent they determine the choices they make.

Obstacles to agroecology that emerged from the study include a lack of land, technology, knowledge, but also prejudice, the absence of a collaborative culture, or simply having different priorities.

A beef farmer: "You ask 'cooperation with other farmers' here, [...] farmers don't cooperate, farmers give each other a hard time."

"They [the nature movement] have their point of view on agriculture, and we have ours. That never goes in. Say it with me: ecology and economics, they don't go together!"

Agroecology made measurable for beef cattle

Louis Tessier's research is also methodologically interesting because he takes important steps to make the concept of agroecology "measurable" in practice. He argues in his doctorate that agroecology is a body of thought rather than a set of specific practices or a legally defined production system. In its most concentrated form, agroecology can be defined as a set of principles, which address both ecological and social dimensions of food systems:

- Strengthen animal health in an integrated way.

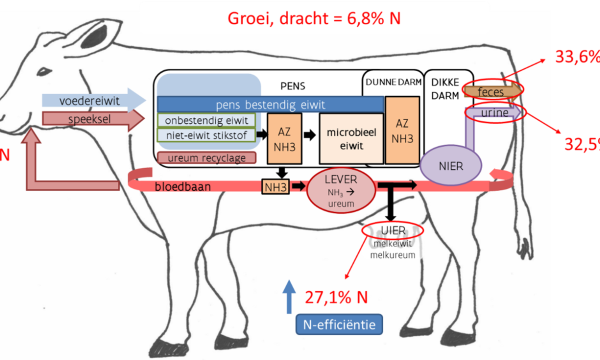

- Close nutrient cycles.

- Maintain high diversity of species and genetic variants over time and space.

- Protect and use biodiversity.

- Reduce the use of external (chemical) inputs.

- Increase ecosystem resilience and adaptive capacity to environmental pressures and shocks.

- Strive for as much independence as possible from influential suppliers or buyers.

- Strive for greater financial independence and control over economic and technical decisions.

- Exchange knowledge with different sources to find problems and solutions.

- Maintain rural social network.

- Collaborate with other producers and consumers.

- Create local food systems of production and consumption.

- Distribute the burdens and the joys of food production equitably.

With these principles in mind, he entered into dialogue with Flemish beef farmers, mapping out 690 potential agroecological practices, from extensive grazing to group purchasing. From this, 36 action paths were defined, each linked to an agroecological principle. This makes agroecology much more tangible in the context of livestock farming.

Agroecology and beef cattle is not a black and white story

By classifying farmers on the basis of these different paths of action, Tessier was also able to break through the typical black-and-white division of farmers: "An important insight from my PhD is that none of the farms fit perfectly into a group. The ideal-typical classifications of farmers that are often used in debates and theories do not fit the reality, because in between there is a broad gray zone of countless farms that integrate various elements of agroecology in their operations. It makes more sense to talk about an economic system in which each farmer tries to find their place, incorporating agroecology if they must or can. Such an understanding of the diversity in beef cattle farming can serve as a basis for a sound, informed debate about the future of beef cattle in Flanders."